Arizona law allows you to sign a “holographic” will (or a holographic codicil). That means you can handwrite your own will and sign it. Such a will or codicil does not need the two witnesses usually required. So that means you can easily write — or change — your will yourself. Right? Please do not try this at home.

Why are we so opposed to holographic wills? Because people get them wrong way too often. Good legal advice is actually inexpensive, and the cost of not getting advice can be high.

Illustrations from our archives

We have written about holographic wills, and how they go wrong, before. In 2014 we described a Florida case involving a holographic will. In that case the legal fees probably exceeded the amount of the inheritance at issue.

While most holographic wills might turn out just fine, the risk is too high for you to write your own will. Besides, it’s more than just writing an effective will — you need advice and help with your entire estate plan. That includes the possibility of a living trust, the need for powers of attorney, and the ideas and experience your lawyer brings to the discussion.

Even when a holographic will is effective, there might be other problems that legal advice could have helped avoid. Have you taken care of beneficiary designations, alternative distributions, and appointment of a personal representative? That’s the kind of thing we (lawyers) focus on.

What about changing an existing will?

Most of the holographic codicil cases we see involve the same basic story. Someone prepares a proper, effective, printed will and signs it in front of two witnesses. Then, months or years later, they want to make a change — often a “small” change. They write something on the will itself, and figure they’ve taken care of the problem that had worried them.

Is that enough? Often it is not. The change they intended to make might even be obvious, and their plan clear — but the change might not be effective.

When a handwritten change to a will is signed, it might qualify as a holographic codicil. That might be true whether the writing is on the will itself, or on a separate piece of paper. Remember that not every state permits holographic codicils, or holographic wills. Arizona does, and so does North Carolina.

A recent case about a holographic codicil

James Paul Allen lived in North Carolina. He had gone to a lawyer to prepare his will, and it was properly printed out, signed and witnessed. It left his entire estate to a long-time girlfriend. If the girlfriend died before him, Mr. Allen’s will provided that one parcel of real estate would go to his girlfriend’s granddaughters — but with a life estate for a nephew, Melvin Woolard.

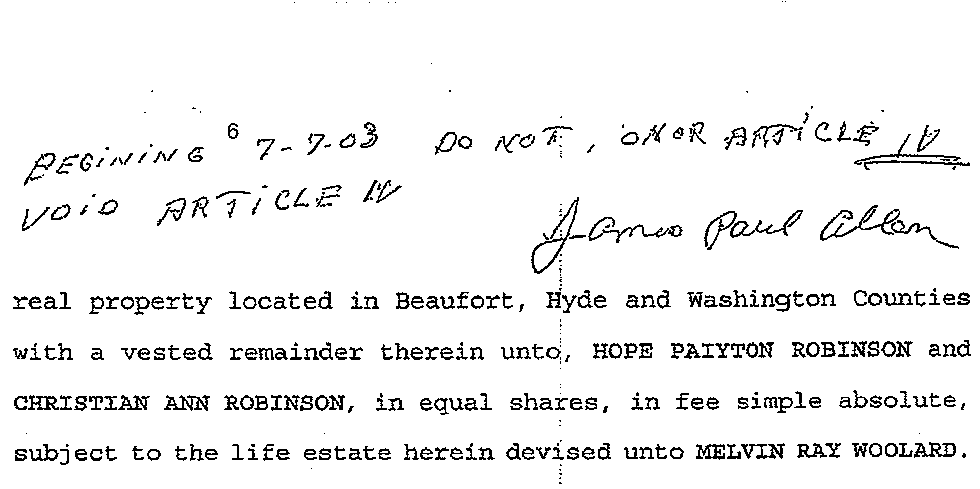

Mr. Allen’s girlfriend died sometime after he signed his will. When the will was located, it looked like he had written on the original document: “Beginning 7-7-03 do not honor Article IV Void Article lV James Paul Allen.”

Article IV of Mr. Allen’s will was the one that had left a life estate in the real estate to his nephew Mr. Woolard. Did that mean that he had amended his will to delete that life estate? If so, his girlfriend’s granddaughters would get the real estate right away; if not, Mr. Woolard would be entitled to live in, rent and otherwise control the property for the rest of his life.

North Carolina court proceedings

Mr. Woolard filed a petition in the probate court, arguing that Mr. Allen had effectively signed a holographic codicil. The probate judge agreed, and ruled in his favor; he would receive a life estate in the property.

The North Carolina Court of Appeals disagreed. According to that court, there were at least two problems with Mr. Allen’s handwritten change. First, it seemed to indicate it would be effective at a future date. Assuming it had been written before July 7, 2003, it said it was to become effective on that date — and that was not permitted under North Carolina law.

The appellate court also found the handwritten note ineffective for another reason. Even assuming it was written by Mr. Allen, it referred to the language in Article IV of the original, printed will. That meant that it was incorporating a non-handwritten provision. In fact, according to the Court of Appeals, the modification could not be understood without reference to the printed portion of the will.

The appellate court sent the contest back to the probate court, ordering that it enter judgment in favor of Mr. Allen’s nephew. The handwritten notation was completely ineffective — even if it actually had been written by Mr. Allen, and even if it had been clear that he intended not to leave any share to Mr. Woolard. In the Matter of the Will of Allen, June 6, 2017.

Arizona law

Arizona, like North Carolina, permits holographic wills and would recognize a holographic codicil. The key provision is found in Arizona Revised Statutes section 14-2503. The requirements are actually quite simple: the document or change must be in the person’s own handwriting, and must be signed. The hardest part: the handwriting must include the “material provisions” of the will or codicil.

So would Mr. Allen’s handwritten note have been effective under Arizona law? Possibly. The North Carolina decision was based on what Arizona courts would likely see as a pretty narrow interpretation. But that uncertainty is precisely why you should not rely on handwritten notes on your will to make intended changes.

On the other hand, perhaps Mr. Allen intended to confuse and annoy his heirs and beneficiaries, and to cost them significant legal expenses in pursuing their interests. In the unlikely case that he intended that effect, he would have done a heck of a job.